Lunch break at a Superfund site

a call to action

Some cities have a sordid past with redlight districts or speakeasies. In St. Louis, the past harks back to an industrial era when it was thriving - the center for steel, car manufacturing, and supplies to the Manhattan Project. But there's a shadowy past that we can either choose to learn from or collectively forget.

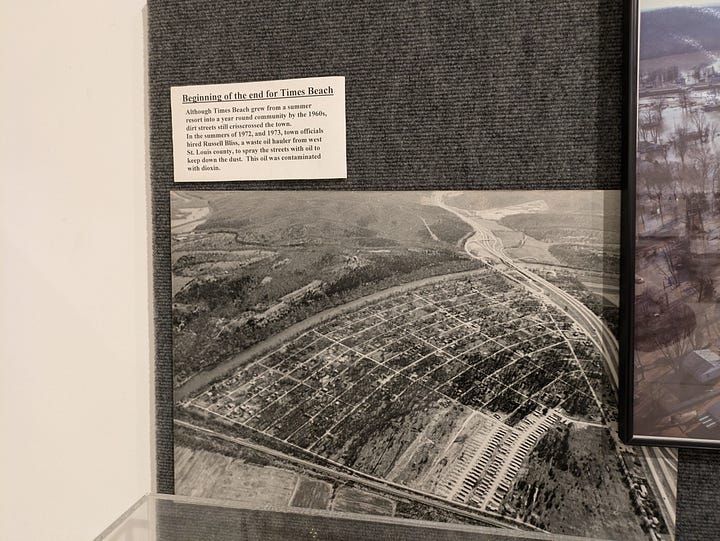

I took a bit of a hike to a little known disaster-turned-state park. Almost 100 years ago the St. Louis Times newspaper sold land lots in this resort area to the public for $67.50 with the purchase of a six-month subscription to its paper. Though the summer retreat, named Times Beach, never quite took off as wanted, it became home to 2,000 middle class people.

In December 1982 the town of Times Beach lived through the horrors of not just one disaster but two: a flood and a subsequent environmental catastrophe. After the flood they realized that the material used as a dust suppressant on the town's dirt roads in the 1970s is waste oil mixed with dioxin.

Dioxin - bi product of Agent Orange manufacturing used for military purposes

Everyone was evacuated from the flood and told not to return home by the CDC and newly formed EPA. There's a chilling account from the newspaper that really brings home the disruption this caused to a working class American town.

People with mortgages and blue collar jobs were unable to return to Christmas at their homes. The following year, there's a federal buyout of the town totaling 800 homes and 30 businesses at a cost of $30M. That's a long time to go with uncertainty of where to live and how to protect your family from an invisible Silent Spring. This was a double tragedy.

Credited with spurring the creation for the Superfund law it actually occurred 2 years following the Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) of 1980 which holds responsible those who create waste, from "cradle to grave." This cleanup took $50M + $120M incineration combined with other sites and is a prime example of what happens if we don't have laws pushing for corporate responsibility and holding accountable the creators of hazards. This should be triggering for you if you think about what is lacking from our PFAS rhetoric in today's politics.

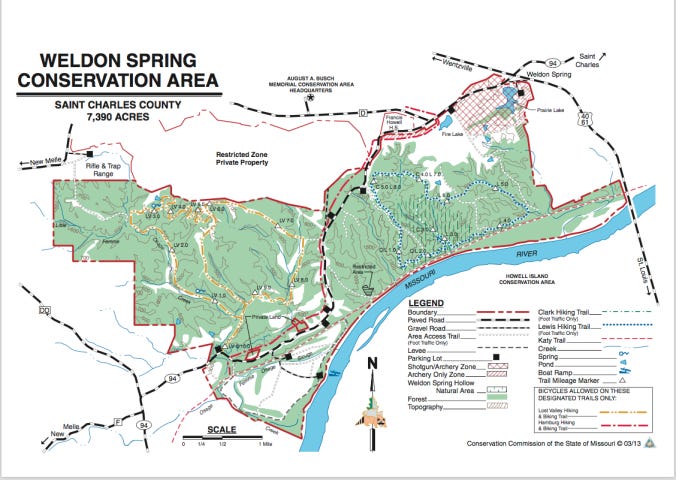

The weekend prior, I drove an hour north of Times Beach. I cycled along the Katy Trail, another marker of our industrial past. This trail is 240 miles across Missouri following the Missouri-Kansas-Texas railroad line (hence the name KATY.) A stone's throw from the Missouri River on the south side, you are even closer to the hidden Hamburg Quarry.

It has suspected radioactive materials but no real investigative journalism or federal attention has been given to the area. Normally I wouldn’t think twice about some bodies of water that are unpermitted to swim that I would love to jump into -- this isn't one of them.

Unanswered questions lead to city-wide rumors…which clearly are not stopping the quarry partying. And it's a missed opportunity for a rehabilitation of a gorgeous natural site that, I believe, should go back to the people.

It’s not unusual for a Superfund site to become a park. The Lipari Landfill is an example. After 4 decades and $100-300 Million in investment, it is no longer a Superfund site including the creeks, aquifers, and surrounding areas. Before you celebrate, taxpayers had to foot this bill to return the nature back to health because we didn't have the legislative foresight or corporate social governance to prevent these situations from happening in the first place.

Look, the quarry is obviously close to groundwater since you can see the MO River from the bluffs where people used to cliff dive into the potentially contaminated quarry water. If there's any site that needs a final chapter, it's this one.

Conservation where there was disaster

There are other industrial quarries immediately along this trail. The best known one contains processed uranium from nuclear pharmaceuticals that were disposed into the Weldon Springs Quarry, an agreement with the feds to own the cleanup in the 1990s by the Dept of Energy. Both the Weldon Springs quarry and uranium-processing plant are located in St. Charles (the historic capital of Missouri, just north of St. Louis across the Missouri River near the start of the Katy trail.) We will always have industry in the country.

Our legacy is how we choose to safeguard potential hazards for future generations.

Take this additional example: further off the Hamburg trail is the TNT disposal cell, a remnant of the industry during WWII. Complete with visitor's center, natural wetlands trail, and walking path to the top it's… still a bit boring. I got quite a kick out of the informational boards which read to me like a scope of work (SOW) for the containment project. It brought me right back to being an engineer-in-training taking groundwater samples and leachate samples from under a haz landfill.

Environmental concerns can become conservation efforts. It's a great solution to take a previous eyesore and bring community, nature, and climate action together. In California, there's the world's largest landfill (video is worth a watch if you’re an engineering geek! but keep in mind that not all countries participate in the practice of landfilling) which is a multi-functional nature reserve for the community.

Normally reclamation refers to taking back land from the sea or wetlands. However, in this case we are taking it back from our anthro-derived past decisions.

How do we memorialize the past?

Oversight on the hazards, poor regulatory environment, and no social corporate governance have led us here. Which begs the question… how do we feel about this today? Under consent decree in 1990, the feds paid for long term management of the Times Beach site and the defendants paid for the structures and disposal, construction of a ring levee to protect the incinerator subsite, temporary incinerator, excavation of contaminated soils, operation of incinerator, and restoration of Times Beach. This site would eventually treat materials from 27 eastern Missouri dioxin sites which spiraled into a community issue. The incinerated remains are buried in the visible mounds.

Today we've started to see the water utilities get pressure to treat PFAS. As a licensed engineer, I agree that utilities need to be realistically responsible for safeguarding public health. But we cannot forget to make the companies that created the hazards responsible for cradle-to-grave of the contaminants which drove their profits. Otherwise, it’s taxpayers footing the bill for corporations. Again.

In 1996 they created Route 66 State Park and today the only evidence of contamination are these eerie mounds around the site. It's a beautiful green space for biking and fishing with access to the Meramec River, an absolute gem of Missouri. And those Christmas decorations? They're buried in the "town mound" where you can frolic with your dog.

Call to Action for St. Louis

For me, this is still a tragedy. A blemish on our history that these working class families were subjected to the horror caused by a corporation without a conscious. I am glad to see it reclaimed to nature and to the people. I would love to see more investigation done into sites that clearly need a new chapter, like the Hamburg Quarry. And I want it be known to visitors the history they are standing on while they're there partying or walking their dog on top of someone's burned Christmas decorations.

Listening: ACL weekend live stream and finding new artists like Stephen Sanchez, FLETCHER, and Connor Price.

Working: Prepping to interview some badass panelists on the water panel at Year in Infrastructure.

Reading: Finding how walkable cities really are https://close.city/